Starting on the same page: Using collaboration agreements to kick off a project

When projects start without clarity, misaligned expectations derail progress before it even begins. One day you’re excited about a new project, the next you’re in a meeting wondering who’s supposed to be doing what to keep things moving. A simple collaboration agreement, completed individually by each teammate and then reviewed together, can spark conversations about roles, responsibilities, and ways of working that align everyone from the start and make projects successful.

This concept isn’t new. Collaboration agreements have helped companies like Spotify improve collaboration, reduce decision-making friction, and enhance product quality (spotify.design). And they’ve even proven to create revenue growth at Apple (Harvard Business Review). What is new is the urgency around them. With AI reducing barriers to creation and blurring traditional role boundaries, teams need explicit agreements more than ever. We’re seeing it play out in real time with PMs, engineers, and designers all prototyping products in tools like Figma Make. Generally, this is a good thing. It leads to more collaboration, which leads to more ideas. But it also creates friction.

When everyone can do a bit of everything, who actually owns what?

Collaboration agreements address this head-on. They're lightweight frameworks that make implicit expectations explicit before work begins. (Or sometimes after you’ve started but realized how messy things are. No judgment. We've all been there.)

What makes an agreement effective

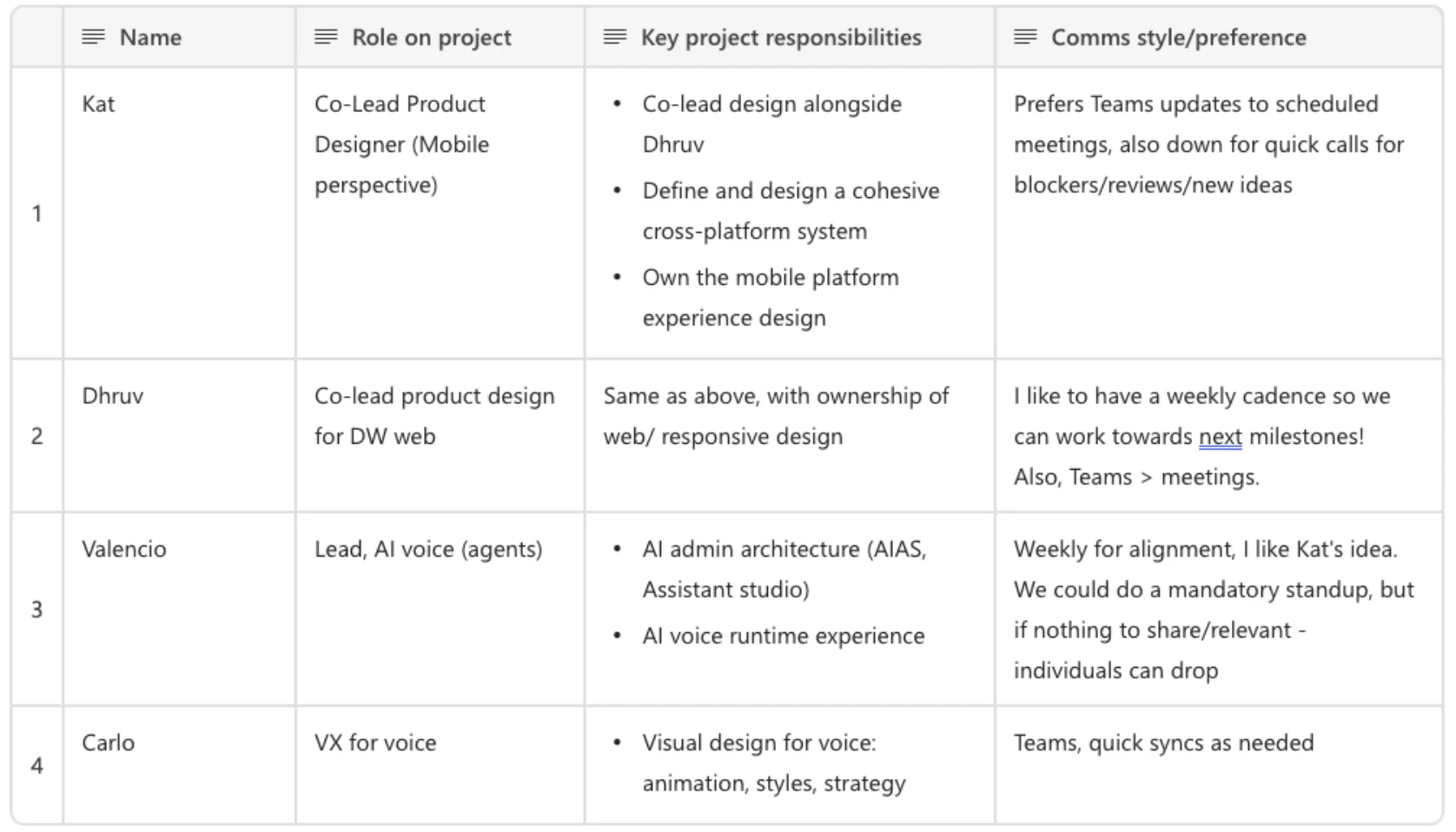

The most useful agreements are simple. Create a table with columns for each teammate’s name, role, project responsibilities, communication preferences, and what they’ll use AI for. Each person fills out their own row.

Here’s an example from ServiceNow’s voice input project which spanned across multiple designers all working toward the same things across platforms:

Roles and responsibilities in a collaboration agreement

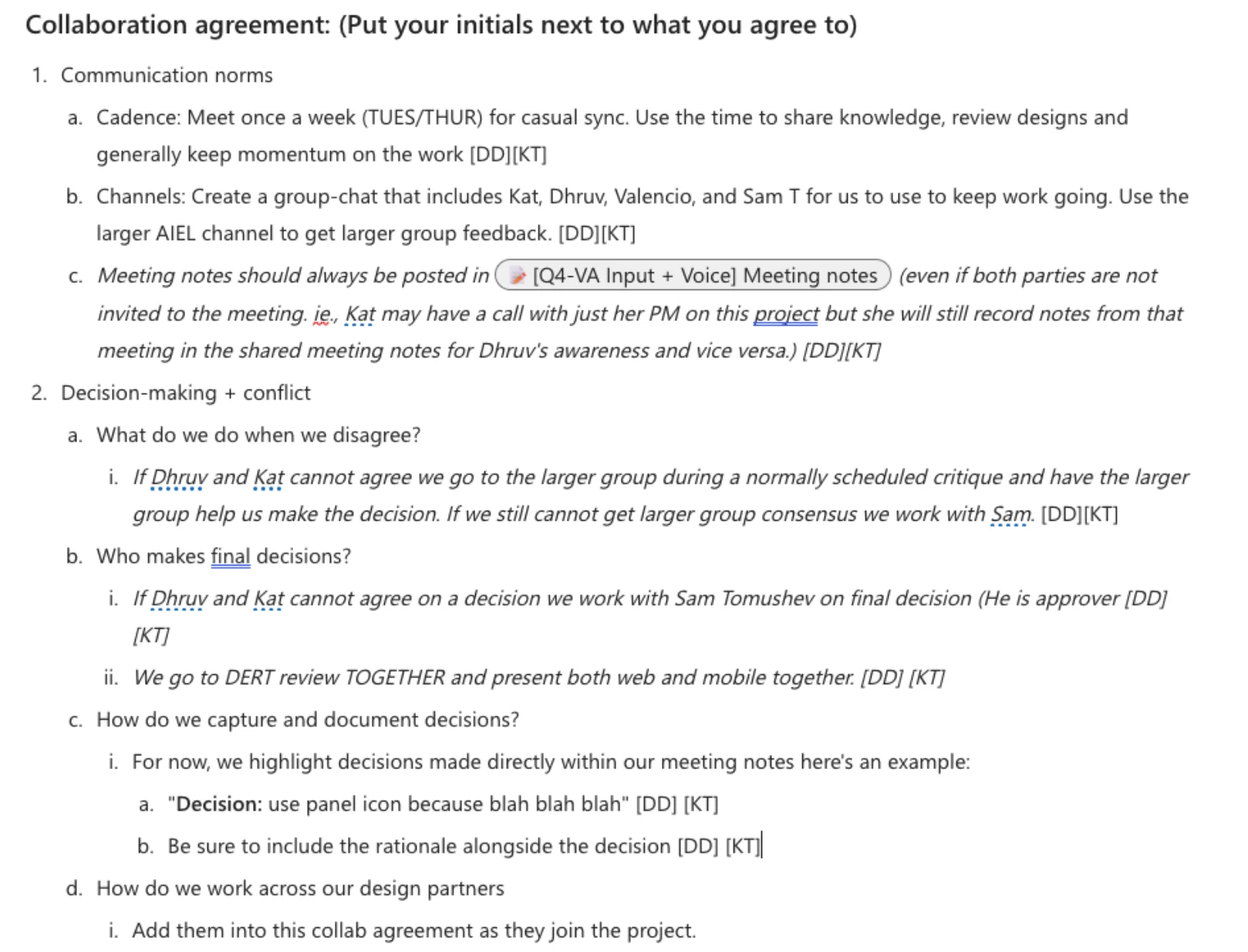

After you’ve taken time to understand the role each of you play, you’ll draft shared statements covering:

- Communication norms: expected cadence, preferred channels, async vs. sSync preferences

- Decision-making: who has final say on what, how you handle disagreements, how you document decisions

- AI use: how and when the team plans to use AI tools, what requires human judgement

Schedule 15 minutes to review everything together, discuss points of misalignment, and have everyone initial the agreements. Then choose a cadence to revisit it, treating it as a living document rather than a one-time exercise.

Here’s an example of the collaboration agreement statements we created and initialed as part of that same project from earlier:

Collaboration agreement statements

At ServiceNow, I’ve used collaboration agreements to help clarify co-leadership on cross-team AI projects. With designers from multiple teams contributing, the agreements help clarify roles like:

- who to contact for what

- which meetings required everyone’s presence, and

- how decisions would escalate.

The result? Reduced noise for contributors who didn’t need to be in every conversation, alignment across 4 different teams all working with different stakeholders, and clearer accountability for managers tracking the work. Our collaboration agreement created a shared view upfront that helped us work together and create quality experiences across surfaces.

“The agreement provided an excellent collaborative structure for everyone on the team! At the onset, it offered clarity on scope, roles, and timeline. Then throughout the design process it allowed us to thoughtfully distinguish between discussions and decisions, which streamlined our teamwork.” - Dhruv Damle, Senior Product Designer

Experimental territory

The “How we intend to use AI” section of the agreement doc is still experimental territory. It’s something new to be incorporated, but the rationale is compelling. With AI capable of generating prototypes, writing code, and drafting content, teams need to be explicit about where humans add irreplaceable value. It’s imperative that we think about how AI fits into our work at every step. Many organizations already have guidelines from enablement teams about AI use. But guidelines are different from practice. Teams are experimenting with how to use AI to get their work done. One person might be using AI to draft specs. Another is prototyping with AI. Someone else is generating test data or refactoring code with AI.

These experiments are happening in the background of “real work,” often invisibly. The sooner we acknowledge that and make it explicit, the better.

What the AI column does is surface those different approaches before they create friction. It’s one thing to discover mid-project that your PM has been using AI to generate mockups while your designer expected to own that work. It’s another to name it upfront: “I’ll use AI to explore rough concepts, then hand off to design for refinement.” This column also serves as inspiration for new ways of using AI. We all bring different lenses to the work we do and those lenses shape the way we approach using AI to get work done. We should leverage this column to learn from each other faster than our enablement teams can give us how-to guides.

And it’s not just about tools. With AI increasingly framed as a “teammate” in product development (something that can generate, iterate, and even ship alongside humans), teams need to be precise about where AI adds value and where human judgement remains essential. The agreement creates space to ask: What parts of this project benefit from AI speed? What parts need our taste, context, and intention?

To be clear, you're not creating rules or policing AI usage here. The goal is to make visible what’s already happening, so teams can learn from each other’s experiments and avoid stepping on each other’s toes. We’re still figuring out the role of AI in product work, but having a column in your collaboration agreement to explicitly discuss it means you’re figuring it out together.

When agreements work

The difference between agreements that stick and those that become shelf documents comes down to a few factors. Some tips for crafting your statements:

Be specific about behavior. Instead of “we’ll communicate openly,” try “we’ll use Teams for quick questions, Microsoft Loop for documenting decisions...” (Specificity sounds boring until you realize it's the thing that actually makes stuff work)

Build accountability into it. Regular check-ins prevent drift. Review the agreement at a regular cadence to remind people about how you agreed to work. It’s okay to revise it if it’s not working.

Be willing to revise. Effective teams treat agreements as hypotheses to test and refine based on what’s actually working. The goal is not to set yourself into an optimized new process, the goal is to document how you work together and have accountability to keep momentum.

Reference it in real time. Use the agreement to reinforce the framework or keep people accountable without feeling heavy-handed. You all agreed to it.

Collaboration agreements work best when teams need them the least. High-trust teams with good communication patterns benefit most because hey use agreements to optimize what’s already working. Teams with deep dysfunction won’t fix fundamental issues with a document. But most teams fall somewhere in between. They’re functional but not optimized.

People often have good intentions but unclear expectations. That’s where agreements deliver the most value. They prevent the small misalignments that compound into large ones.

Give it a shot

If you’re starting a new project, try creating a collaboration agreement as part of the kickoff call. If you’re mid-project and things feel misaligned, use it as a diagnostic tool. Where do your current practices diverge from what you’d write down? Those gaps reveal friction points worth addressing.

The goal is conscious alignment. Getting everyone pointing in the same direction, aware of where responsibilities overlap and where they don’t, clear about how decisions get made when time is tight.

Fifteen minutes of setup can save hours of confusion later. Collaboration agreements won’t fix everything, you still have to do the work and communicate, but at least you’ll know who’s doing what. And honestly, that’s half the battle.